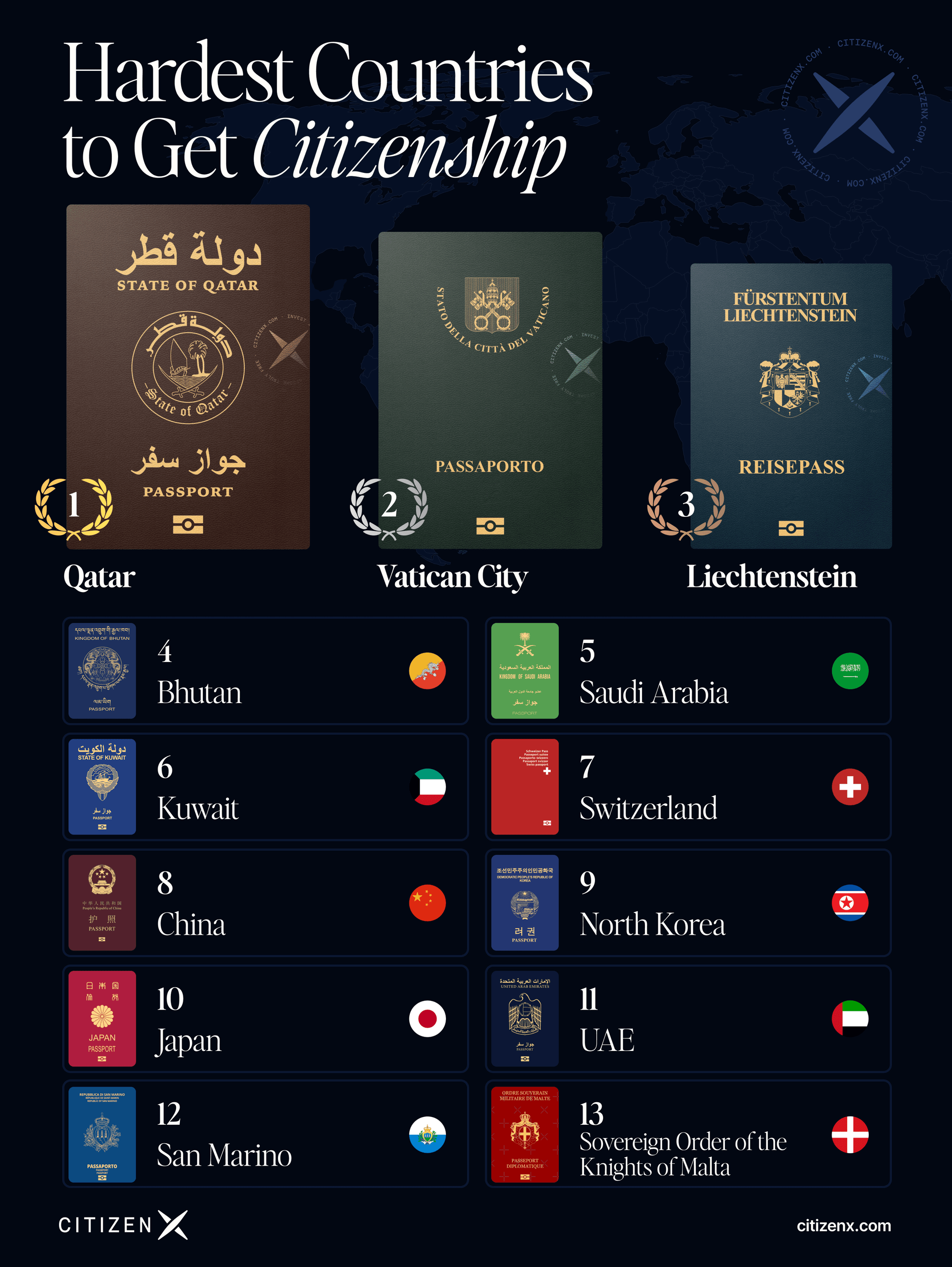

The World's Hardest Countries to get Citizenship in 2026

This comprehensive analysis examines the citizenship requirements of 13 of the world's most restrictive jurisdictions as of 2026, revealing how cultural preservation, demographic concerns, and national security shape policies that effectively close borders to new citizens.

In an era of increasing global mobility, a select group of nations maintains citizenship policies so restrictive that naturalization remains virtually impossible for most applicants.

These countries protect their national identity through complex requirements, decades-long residency mandates, and near-zero approval rates that stand in stark contrast to the growing trend of citizenship-by-investment programs offering passports within months.

This comprehensive analysis examines the citizenship requirements of 13 of the world's most restrictive jurisdictions as of 2025, revealing how cultural preservation, demographic concerns, and national security shape policies that effectively close borders to new citizens.

From the Gulf states' protection of citizen privileges to European micro-states' unique approval systems, these nations demonstrate that citizenship remains one of the most exclusive clubs in international affairs.

The Impenetrable Gulf: Where Oil Wealth Meets Demographic Anxiety

The Gulf Cooperation Council countries represent perhaps the most restrictive citizenship policies globally, with naturalization rates approaching zero despite hosting millions of expatriate workers. These nations maintain stringent controls to preserve the economic and social privileges of their small citizen populations.

Qatar's Calculated Exclusivity

Qatar exemplifies Gulf citizenship restrictions with its 25-year consecutive residency requirement and annual naturalization cap of approximately 50 people. Despite expatriates comprising 88.4% of the population, the pathway to Qatari citizenship remains virtually closed. The nation requires uninterrupted residence with no absences exceeding two consecutive months annually, Arabic proficiency, and demonstration of integration into Qatari society.

Recent policy changes have created a two-tier citizenship system where naturalized citizens cannot vote or hold elected office, effectively creating permanent second-class status. The 2024 addition to the US Visa Waiver Program and new entrepreneur visa initiatives signal economic openness without citizenship access. Investment provides only a residency pathway through the QAR 3.65 million (approximately $1 million) permanent residency program, with no direct route to naturalization.

Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030 Paradox

Saudi Arabia presents an intriguing contradiction: ambitious economic diversification plans alongside highly restrictive citizenship policies. The Kingdom's Premium Residency program, expanded in January 2024 with five new categories, offers pathways ranging from SAR 100,000 ($26,670) annually to SAR 15 million ($4 million) for entrepreneurs. Yet actual naturalization remains extraordinarily rare, with approval numbers classified by the government.

The point-based system requiring a minimum of 23 points favors Muslim applicants with strong Arabic skills and cultural compatibility. Since November 2021, the Kingdom has begun granting citizenship to "exceptional talent" including scientists, researchers, and healthcare professionals, though exact numbers remain undisclosed. All successful applicants must renounce previous citizenships within six months, as dual nationality results in automatic loss of Saudi citizenship.

Kuwait's Reversal of Rights

Kuwait demonstrates how citizenship policies can become more restrictive over time. The December 2024 amendments through Decree 116/2024 eliminated the marriage pathway for foreign women and ended automatic eligibility for wives of naturalized citizens. Most dramatically, Kuwait has revoked over 42,000 citizenships between 2024 and 2025 in a massive denaturalization campaign reversing earlier political naturalizations from the 1980s.

The standard requirements remain daunting: 20 years for non-Arabs versus 15 years for Arab nationals, with mandatory Arabic proficiency and Islamic faith. Uniquely, naturalized citizens cannot vote for 30 years after obtaining citizenship, and apostasy from Islam results in automatic citizenship loss. The country's Bedoon crisis continues with over 100,000 stateless residents denied citizenship despite generational presence in Kuwait.

UAE's Exceptional Merit Innovation

The United Arab Emirates stands apart among Gulf states with its January 2021 landmark amendment allowing exceptional merit citizenship for non-Arabs. This represents the region's most progressive citizenship policy, though standard naturalization still requires 30 years of continuous legal residency. The exceptional merit categories include doctors with 10+ years experience, scientists, inventors, investors, and cultural figures.

The Golden Visa program offers residency options from AED 500,000 ($136,000) for entrepreneurs to AED 10 million ($2.72 million) for public investments. Unlike other Gulf states, the UAE permits dual citizenship for exceptional merit recipients and their families. However, with Emiratis comprising only 12% of the population, actual naturalization numbers remain minimal, estimated at dozens annually.

European Micro-States: Democracy Meets Exclusivity

Europe's smallest nations maintain some of the world's most unique citizenship systems, combining democratic principles with practical limitations that make naturalization extraordinarily difficult.

Vatican City's Ecclesiastical Exception

Vatican City operates the world's most exclusive citizenship system with only 673 citizens among 882 total residents. Citizenship is entirely function-based, tied to employment within the Vatican or service to the Catholic Church. Cardinals residing in Vatican or Rome, Holy See diplomats, Swiss Guard members, and those with papal permission qualify for temporary citizenship that ends with their service.

No traditional naturalization process exists, and all residents must be Catholic. The May 2023 Fundamental Law reinforced these restrictions, emphasizing that citizenship remains limited to those essential to Vatican functions. Children of citizens lose their status at age 18 unless they meet specific conditions. Remarkably, Vatican citizenship is typically held alongside original nationality, as the temporary nature precludes requiring renunciation.

Liechtenstein's Referendum Barrier

Liechtenstein exemplifies how direct democracy can create insurmountable naturalization barriers. Despite relatively modest residency requirements of 10 years for ordinary naturalization, applicants must pass a municipal referendum where existing citizens vote on each application. This system results in one of the world's lowest naturalization rates, with only 189 foreign nationals naturalized in 2023 from a population of 39,584.

The facilitated naturalization path requires 30 years of residence but bypasses the vote. An August 2020 referendum rejected dual citizenship by 61.5%, maintaining mandatory renunciation requirements. Municipal voting patterns show extreme reluctance to approve applicants with less than 30 years residence, making the democratic process a de facto prohibition on naturalization for most long-term residents. B1 German proficiency and deep community integration are prerequisites that many still find insufficient for voter approval.

San Marino's Parliamentary Gatekeeping

San Marino requires one of the world's longest residency periods at 30 years for standard naturalization, reduced to 10 years for those married to citizens. Beyond these requirements, the Grand and General Council must approve each application with a two-thirds majority, creating a political barrier that results in fewer than 50 naturalizations annually.

The country offers sophisticated residency-by-investment programs starting at €500,000 for property purchase or €600,000 in bank deposits, but these provide no pathway to citizenship. Mandatory renunciation of previous citizenship and parliamentary approval combine to maintain one of Europe's most exclusive citizenship policies. Italian language proficiency and integration into San Marino society are expected but often insufficient for approval.

Sovereign Order of Malta's Unique Sovereignty

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta represents the world's only sovereign entity without territory, issuing approximately 500 diplomatic passports linked to specific assignments. Membership in the Order, a prerequisite for any documentation, requires Roman Catholic faith and invitation-only acceptance based on charitable service and exemplary morality.

The Order issues roughly 155 new passports annually for diplomatic missions and humanitarian work in dangerous areas. While 115 states recognize these documents, they don't confer traditional citizenship but rather functional diplomatic status. The three classes of membership reflect varying requirements from nobility for Knights of Honour and Devotion to merit-based acceptance for Knights of Magistral Grace.

Skip the grind: Malta (EU) citizenship

Secure EU citizenship via Malta’s MEIN route.

Asia's Ethnic and Ideological Barriers

Asian nations present some of the world's most ethnically and ideologically restrictive citizenship policies, with several countries maintaining near-zero naturalization rates despite large foreign populations.

Bhutan's Cultural Purity Doctrine

Bhutan's citizenship laws, rooted in the 1985 Citizenship Act, effectively exclude non-ethnic Bhutanese from naturalization. The expulsion of 100,000-150,000 Lhotshampas (ethnic Nepalis) in the 1990s for failing cultural requirements demonstrates the extreme application of these policies. Requirements include 20 years residence for non-government employees, fluency in Dzongkha, knowledge of Driglam Namzha (national customs), and the King's personal approval through a "Royal Kasho."

Both parents must be Bhutanese citizens for automatic citizenship by birth, and dual nationality is strictly prohibited. The emphasis on Buddhist cultural heritage and the "One Nation, One People" policy create insurmountable barriers for non-ethnic Bhutanese, making this one of the world's most ethnically exclusive citizenship regimes.

China's Minimal Naturalization Reality

Despite being the world's second-largest economy, China maintains one of the lowest naturalization rates globally. The 2010 census recorded only 1,448 naturalized citizens among 1.34 billion people—a rate of 0.0001%. Requirements include permanent residency (itself difficult to obtain), close relatives who are Chinese nationals, or "other legitimate reasons" interpreted at official discretion.

Recent reforms have introduced more systematic approaches in cities like Shanghai, where PhDs can obtain permanent residency immediately, and created 13 immigrant categories. However, the 2023 statistics showing only 16,600 new citizens registered demonstrate continued restrictions. Mandatory renunciation of previous citizenship and strong preference for ethnic Chinese ancestry maintain barriers even for long-term residents.

North Korea's Information Black Hole

North Korea operates the world's most secretive citizenship system, with requirements undisclosed and naturalization virtually impossible for non-ethnic Koreans. The 1963 Nationality Law claims all overseas Koreans as citizens, but practical naturalization remains limited to historical cases including Soviet Koreans, ethnic Chinese (Hwagyo), and Japanese wives of repatriates.

Citizenship is tied to the songbun caste system, and leaving the country without permission is illegal. While legal frameworks theoretically exist, the complete absence of transparency and diplomatic isolation make North Korea's citizenship among the world's most restrictive. Dual citizenship is not recognized, and renunciation is extremely difficult even for those abroad.

Japan's Cultural Integration Emphasis

Japan's naturalization system, while more transparent than other Asian nations, maintains significant cultural barriers. The general requirement of 5 years continuous residence extends to 10+ years for many applicants, with Japanese language proficiency equivalent to elementary school level required. Despite these requirements, Japan naturalized only 8,800 people in 2023 from 9,836 applications, with most being ethnic Koreans with multi-generational residence.

Recent changes lowered the age requirement from 20 to 18 in 2022, but dual citizenship remains prohibited with mandatory renunciation. Japanese citizens who voluntarily acquire foreign citizenship automatically lose Japanese nationality. The absence of a formal citizenship test belies the extensive cultural integration evaluation during interviews. Special naturalization for exceptional contributions exists in law but has never been used as of 2024.

Switzerland's Federal Maze

Switzerland operates perhaps the world's most complex naturalization system, requiring approval at federal, cantonal, and municipal levels. This three-tier approach means requirements vary significantly across 26 cantons and approximately 2,100 municipalities.

Federal requirements mandate 10 years residence (reduced from 12 in 2018), including 3 of the last 5 years before application. Language requirements of B1 oral and A2 written in a national language apply universally, tested through the standardized "fide" system. However, cantonal variations range from 2 years additional residence in Geneva to 5 years in Zug, while municipal requirements can include community votes, specific local integration, and fees ranging from CHF 500 to CHF 3,000+.

The system's complexity creates significant disparities. Zurich shows a 2.2% naturalization rate since 1998, while Glarus records only 0.6%. The 2018 reforms requiring C permit (permanent residence) status effectively excluded 20% of previous applicants, while data shows university-educated applicants rose from 33.5% to 57% of new citizens, demonstrating the system's tilt toward high-income, educated applicants.

Some municipalities still conduct community assemblies where residents vote on applications, leading to controversial rejections. The Nancy Holten case in Gipf-Oberfrick, where a Dutch woman was initially rejected for opposing cowbells, exemplifies how local prejudices can override legal qualifications. While Switzerland permits dual citizenship, the labyrinthine approval process and subjective local criteria maintain one of Europe's most demanding naturalization systems.

The Citizenship-by-Investment Contrast

The restrictive policies of these 13 nations stand in sharp relief against the growing citizenship-by-investment industry. Caribbean nations have created streamlined programs offering full citizenship within months for investments starting at $200,000. These programs demonstrate an entirely different philosophy toward citizenship, viewing it as an economic development tool rather than an exclusive birthright.

St. Lucia leads with 60-day processing for a $240,000 investment, while Dominica offers the most affordable option at $200,000. Grenada provides unique access to the US E-2 investor visa, and St. Kitts & Nevis maintains the oldest program with the "platinum standard" reputation. Antigua & Barbuda requires only 5 days of physical presence over 5 years, contrasting sharply with the decades-long residence requirements in restrictive countries.

Portugal's Golden Visa program, despite eliminating real estate options in 2023, continues offering EU residency leading to citizenship after 5 years for investments starting at €500,000. El Salvador's innovative Bitcoin citizenship program, requiring $1 million in cryptocurrency, represents the newest frontier in investment migration.

These programs' success—with some Caribbean nations deriving over 20% of GDP from citizenship sales—demonstrates the economic potential of accessible naturalization. Application approval rates of 95-99% for properly prepared cases contrast dramatically with the near-zero rates in restrictive countries.

Divergent Philosophies in a Modern World

The stark differences between restrictive and accessible citizenship policies reflect fundamental disagreements about the nature of national belonging in the 21st century. Restrictive nations prioritize cultural homogeneity, demographic balance, and citizen privileges, viewing naturalization as a rare exception requiring decades of proven loyalty. Countries like Bhutan explicitly use citizenship law to maintain ethnic purity, while Gulf states protect economic advantages for small citizen populations.

In contrast, citizenship-by-investment programs embrace a transactional view where economic contribution can substitute for cultural integration or long-term residence. This divide raises profound questions about whether citizenship represents an immutable birthright or a status that can be earned, purchased, or revoked based on changing national interests.

Recent trends show some movement in both directions. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have created exceptional talent categories, recognizing that absolute restrictions may hinder economic development. Conversely, Kuwait's mass denaturalization campaign demonstrates how citizenship can be weaponized for political purposes, while Caribbean nations' raising of minimum investments shows growing concern about program integrity.

As global mobility increases and remote work normalizes, pressure will mount on restrictive nations to reconsider absolute barriers to naturalization. However, the persistence of these policies—some unchanged for decades—suggests that for many nations, citizenship will remain an exclusive privilege rather than an attainable goal, regardless of an applicant's contributions, integration, or dedication to their adopted homeland.

The 13 nations examined here stand as fortresses of exclusivity in an increasingly interconnected world, maintaining citizenship policies that effectively say to the vast majority of humanity: you may live here, work here, even die here, but you will never truly belong.

For those seeking more accessible pathways to second citizenship, explore CitizenX's comprehensive citizenship by investment programs that offer transparent, efficient routes to new nationalities within months rather than decades.